Vascular Theory Exams 2024

16th July 2024

This is the third part of the SVT Research Series continuing from ‘A Roadmap to Research’ in the Winter Newsletter and ‘Identify & Define the Research Question’ in the Spring Newsletter. In this article, we describe the process of undertaking a literature review.

When a topic of interest is decided upon and the research question is being developed, it is important to grasp the current knowledgebase and to identify the research gap. A Literature Review is the process by which the current evidence relating to a topic is gathered, reviewed, and assessed. They importantly seek to summarise the available literature, journal papers, conference proceedings etc., to make sense of it as a whole. There are a number of different review types and these are detailed in Noble and Smith (2018).

An informal, narrative review is commonly a part of an essay, dissertation or even research paper and will ‘set the scene’ by way of an introduction. These lead the audience to understand the rationale behind the work being presented. They can also aid in education, continued professional development, or as an initial introduction to a new clinical or research area. A quick search using PubMed or Google can return hundreds or thousands of articles linked to keywords of interest. The task is then to write an overview of the articles found, however, these reviews may not be reliable as the author can select which articles to include to support their hypothesis or point of view. Therefore, this type of review doesn’t fit into the evidence-based practice paradigm that is so important in modern healthcare.

To be able to properly assess the literature and to balance results and conclusions, a systematic review is needed. These can be defined as 'concise summaries of the best available evidence that address sharply defined clinical questions' (Mulrow et al, 1997) and can be seen as a research methodology in their own right.

A formal systematic review follows a structured format and is designed to be robust and reproducible to ensure the minimisation of bias from the literature review process. These systematic reviews can be a seen as a research methodology in their own right. An example of high-quality systematic reviews are those published by the Cochrane Collaboration. The website www.cochrane.org contains much more information and training.

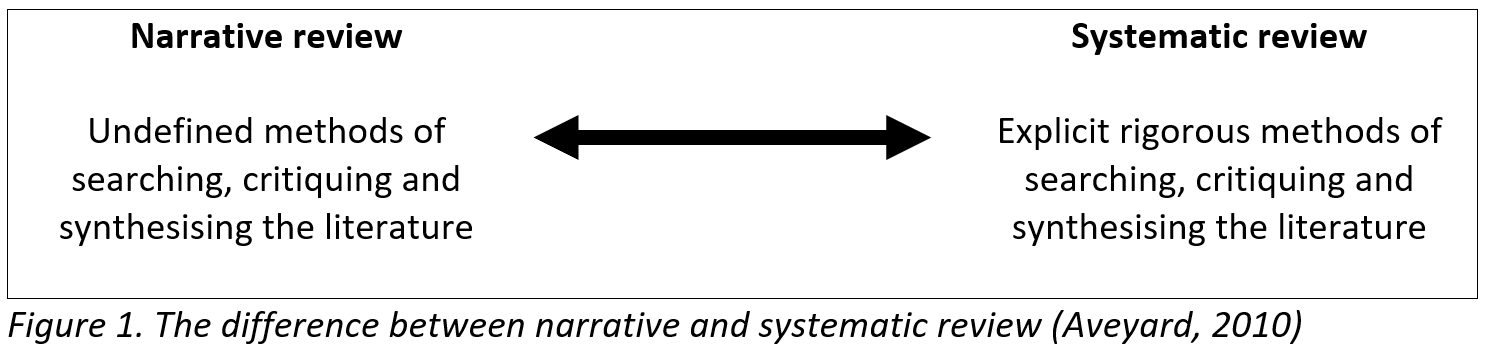

As shown in Figure 1, the literature review can be seen a spectrum from the informal narrative review to the high-quality systematic review. However, rigorous reviews can be very demanding on time and personnel and are often out of reach for early career researchers.

|

Here, we give a brief overview of the various aspects of a systematic review, but less rigorous than a Cochrane review. The stages of a systematic review include:

A good research question must be focussed and clinically applicable. An example of a framework for question development is PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome). More information on this will be described in the next part of our series.

To be able to find the relevant work a robust and comprehensive search strategy must be defined and carried out, as well as detailing the eligibility criteria for the inclusion or exclusion of studies/papers. This is done to avoid potential 'cherry-picking' of studies that can happen in narrative reviews. Many of us use Google for everyday and even work-related searches. However, for a literature review it is normal to focus on online specialist electronic databases to carry out your search. These databases include PubMed, CINAHL and Web of Science, etc.. Additionally, searching for specific authors, centres or professional groups can identify literature that may not have been found with keywords. Reference lists of other reviews and articles can also be hand searched for additional studies.

A brief example may be of the search strategy:

When a reference list of papers is compiled then the title and/or abstract can be read to determine relevance to your research question. However, it has been found that title and sometimes even the abstract are not always reliable enough to include or exclude the paper from your review.

The next stage is to get hold of all the relevant papers on your list. This can prove difficult due to access issues, although some will be found in full text on PubMed for example. Many NHS Trusts and HEIs will have access to a wide variety of journals and don't forget that SVT provides access to the European Journal for Vascular and Endovascular Surgery as part of your membership benefits.

When the literature review has been carried out and the papers, conference proceedings, etc. have been obtained, then it is important to critically appraise the published research. More information on this can be found at the CASP website, www.casp-uk.net.

Essentially the critical appraisal process involves reading each paper and then answering the following questions:

This process allows poor quality papers to be excluded or their problems highlighted and accounted for in the discussion. However, it also enables the strengths and findings of good papers to be reported.

When the studies have been appraised, then it is important to select the papers to be included and to very briefly summarise them in a table with details of the parts that relate to your research/clinical question.

Quantitative data can then also used in a meta-analysis, where the results of the many studies are combined to one more powerful result. However, these are usually not appropriate for early career researchers without help from experiences supervisors.

The report of the literature review should follow the usual research paper format:

Abstract; Introduction; Methods; Discussion; References.

Aveyard H. (2010) Doing a Literature Review in Health and Social Care A Practical Guide. 2nd Edition. McGraw Hill.

Greenhalgh T. (2019) How to read a paper: The basics of evidence based medicine. 6th Edition. Wiley-Blackwell.

Mulrow, C et al. (1997) Systematic Reviews: Critical Links in the great chain of evidence. Annals of Internal Medicine. 126(5):389-91.

Noble H, Smith J. Reviewing the literature: choosing a review design. Evidence-Based Nursing 2018;21:39-41.